Teaching Video NeuroImages: Minimal anomalies of dorsal midbrain syndrome (Parinaud syndrome)

Pilar Rojas, Philippe Maeder and François-Xavier Borruat.

Neurology. January 03, 2017; 88 (1) RESIDENT AND FELLOW SECTION

Parinaud syndrome results from posterior commissure dysfunction, and is associated with 4 major signs: limitation of upgaze, pupillary light-near dissociation, convergence abnormalities, and Collier sign.1,2

A 46-year-old man complained of vertical diplopia due to a subtle left skew deviation. Upgaze pursuit was normal, but upward saccades were slowed, without convergence abnormalities or Collier sign (video). Pupillary light-near dissociation was present (video). MRI revealed a tectal mesencephalic lesion (figure).

Figure Brain MRI

T2 axial and coronal cuts (A, C) and T1 sagittal cut with gadolinium (B) revealed a tumor originating from the walls of the third ventricle posteriorly, with an invasion of the posterior commissure (white arrow). The lesion was later biopsied and pathology revealed a pilocytic astrocytoma.

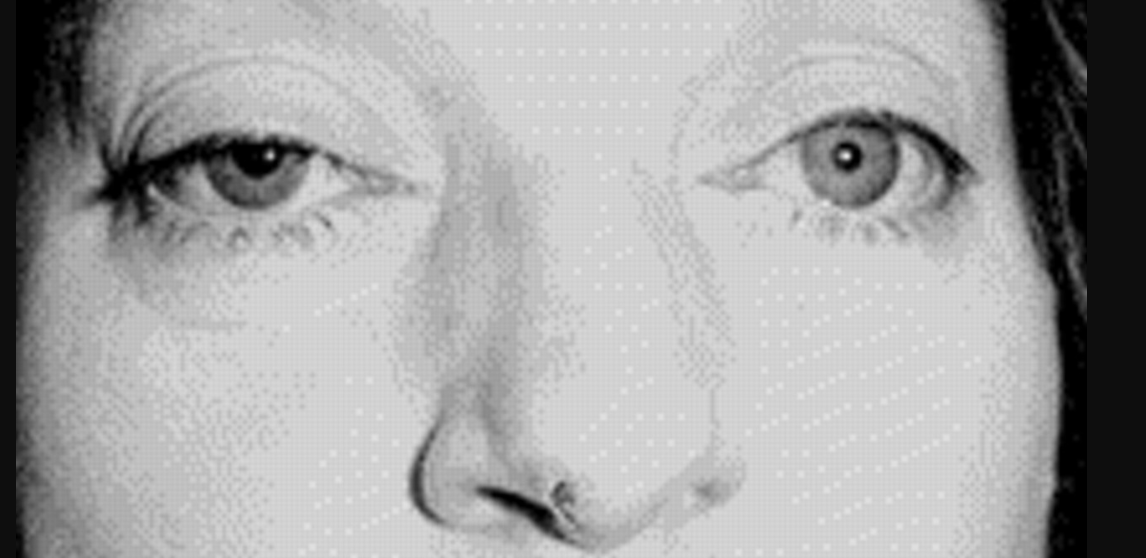

Video Ocular motility and pupils examination.

Horizontal pursuit and saccades, and both upward and downward vertical pursuit were normal in both eyes, namely without any limitation of upgaze. The speed of downward vertical saccades was normal, whereas upward saccades from primary gaze were slowed. The pupils were of intermediate and equal size, and pupillary light-near dissociation was present in both eyes.

Slowed upward saccades and pupillary light-near dissociation represent an early stage of posterior commissure dysfunction, before frank upgaze palsy, Collier sign, or convergence abnormalities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pilar Rojas is an author and contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. Philippe Maeder is an author, contributed to data acquisition, and revised the manuscript. François-Xavier Borruat is an author, contributed to data acquisition, and revised the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Download teaching slides: Neurology.org

REFERENCES

1. Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements, 3rd ed. part II, ch 10. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:517–519.

2. Miller NR, Newman NJ. Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, 5th ed. vol 1, ch 29. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:1304–1311.