Questions:

1. How are 3rd nerve dysfunctions classified?

2. What is the definition of a partial 3rd nerve palsy?

3. What are the two categories of complete 3rd nerve palsies?

4. What is meant by “a pupil-sparing 3rd nerve palsy”?

5. What tests should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated incomplete 3rd nerve palsy and the pupil is involved?

6. What should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated complete 3rd nerve palsy and the pupil is NOT involved?

7. What should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated complete 3rd nerve palsy, the pupil is NOT involved, and has normal lab (Blood glucose, CBC, platelets, ESR, CRP) is followed daily and develops pupillary involvement?

8. What is the most common cause of an isolated “pupil-sparing 3rd nerve palsy”?

9. Are microvascular 3rd nerve palsies painful?

10. What should be ruled-out when making the diagnosis of a microvascular complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing in a patient over 50?

11. What in addition to cranial arteritis should be considered when making the diagnosis of a microvascular pupil complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing?

12. How long does it usually take for a microvascular 3rd nerve palsy to resolve?

13. If a complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing thought to be of microvascular origin does not clear in 4 months what should be done?

14. What test should be done in a patient under age 50 who presents with an isolated 3rd nerve palsy with or without pupillary involvement?

15. Should the pupils of a patient with an acute 3rd nerve palsy with “pupil sparing” be dilated to complete the eye exam?

16. What should be ruled-out in a patient without a history of trauma has signs of aberrant regeneration of the 3rd nerve?

17. What are the symptoms of pituitary apoplexy?

18. What are the findings when there is a unilateral lesion of the entire 3rd nerve nucleus?

19. Why does a complete unilateral nuclear 3rd nerve palsy have bilateral ptosis?

20. Why does a complete unilateral nuclear 3rd nerve palsy have bilateral elevation deficits?

21. What are the findings of a unilateral lesion of the 3rd nerve fascicle?

____________________________________________________

Questions with answers:

1. How are 3rd nerve dysfunctions classified?

They are classified into 3 specific categories:

a. partial (paresis, not a palsy)

b. complete (palsy) WITHOUT pupillary involvement (= pupil sparing)

c. complete (palsy) WITH pupillary involvement.

2. What is the definition of a partial 3rd nerve palsy?

A partial 3rd nerve palsy is when one or more of the extraocular muscles innervated by the 3th nerve are not affected or when there is only paresis of the one or more of these muscles.

3. What are the two categories of complete 3rd nerve palsies?

a. Complete with pupillary involvement.

b. Complete with pupil sparing.

4. What is meant by “a pupil-sparing 3rd nerve palsy”?

A “pupil-sparing 3th nerve palsy” refers only to a complete 3th nerve palsy in which all the extraocular muscle it serves are without any activity and in which the pupil remains of normal size and reactivity.

5. What tests should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated incomplete 3rd nerve palsy and the pupil is involved?

Blood glucose, CBC, platelets, ESR, CRP, Brain MRI with MRA or CTA and often catheter angiography as aneurysms, pituitary lesions and cranial arteritis must be ruled-out.

6. What should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated complete 3rd nerve palsy and the pupil is NOT involved?

Blood glucose, CBC, platelets, ESR, CRP, as cranial arteritis must be ruled-out. These patients must be observed closely for the next week for evidence of pupillary involvement. If the pupil becomes involved neuroimaging to rule-out compressive lesions including aneurysms should be done.

7. What should be done when a patient over age 50 presents with an isolated complete 3rd nerve palsy, the pupil is NOT involved, and has normal lab (Blood glucose, CBC, platelets, ESR, CRP) is followed daily and develops pupillary involvement?

Emergent brain MRI with MRA or CTA and often catheter angiography as aneurysms and pituitary lesions must be ruled-out.

8. What is the most common cause of an isolated “pupil-sparing 3rd nerve palsy”?

The cause of most an isolated pupil-sparing third-nerve palsy is believed to be microvascular ischemia, frequently associated with diabetes mellitus or other vascular risk factors.

9. Are microvascular 3rd nerve palsies painful?

Microvascular 3rd nerve palsies sometimes are quite painful.

10. What should be ruled-out when making the diagnosis of a microvascular complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing in a patient over 50?

Cranial arteritis

11. What in addition to cranial arteritis should be considered when making the diagnosis of a microvascular pupil complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing?

Myasthenia gravis and Wernicke encephalopathy, the two conditions that can mimic any ocular motility disorder with normal pupils.

12. How long does it usually take for a microvascular 3rd nerve palsy to resolve?

They usually resolve after 3 to 4 months.

13. If a complete 3rd nerve palsy with pupil-sparing thought to be of microvascular origin does not clear in 4 months what should be done?

Neuroimaging should be performed to rule-out a compressive lesion including aneurysm if not done initially.

14. What test should be done in a patient under age 50 who presents with an isolated 3rd nerve palsy with or without pupillary involvement?

Brain MRI, MRA or CTA, and consider catheter angiogram and lumbar puncture.

Aneurysm and pituitary lesions must be ruled-out.

15. Should the pupils of a patient with an acute 3rd nerve palsy with “pupil sparing” be dilated to complete the eye exam?

No. Acute 3rd nerve palsies are true neuro-ophthalmic emergencies, especially painful ones. Careful examination of the pupils is essential, and these patients should not be dilated pharmacologically to allow repeated pupillary examinations. These patients must be observed closely (at least daily) for the next week for evidence of pupillary involvement. If the pupil becomes involved neuroimaging to rule-out compressive lesions including aneurysms should be done emergently.

16. What should be ruled-out in a patient without a history of trauma has signs of aberrant regeneration of the 3rd nerve?

Neuroimaging to rule-out compressive lesions.

17. What are the symptoms of pituitary apoplexy?

Pituitary apoplexy classically results in sudden unilateral or bilateral ophthalmoplegia, headache, and often visual loss (from compression of the optic nerves and chiasm).

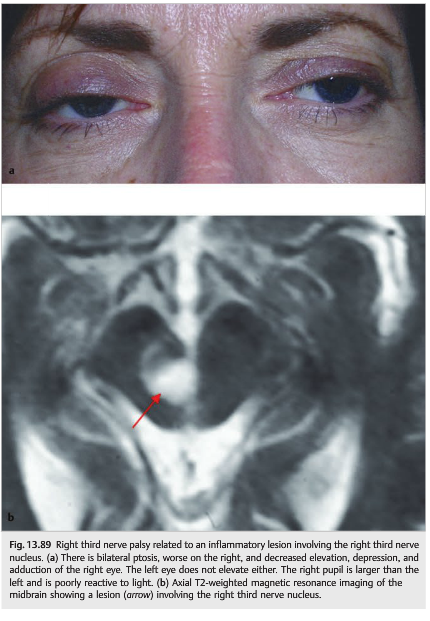

18. What are the findings when there is a unilateral lesion of the entire 3rd nerve nucleus?

a. Complete ipsilateral 3rd nerve palsy with pupil involvement.

b. Bilateral ptosis, and

c. Bilateral elevation deficit.

19. Why does a complete unilateral nuclear 3rd nerve palsy have bilateral ptosis?

A unilateral nuclear lesion of the 3rd nerve affects the single central caudal subnucleus which serves both levator palpebrae muscles.

20. Why does a complete unilateral nuclear 3rd nerve palsy have bilateral elevation deficits?

A unilateral nuclear lesion of the 3rd nerve affects the ipsilateral subnucleus serving the contralateral superior rectus and the fibers from the contralateral subnucleus serving the contralateral superior rectus as they pass through the ipsilateral nuclear lesion.

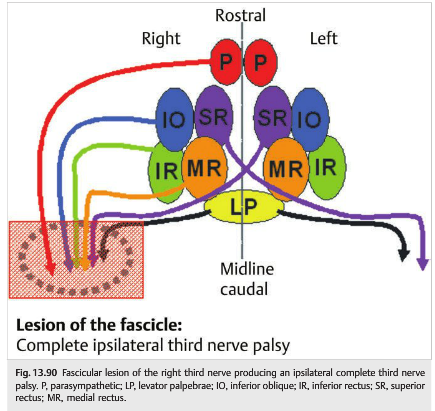

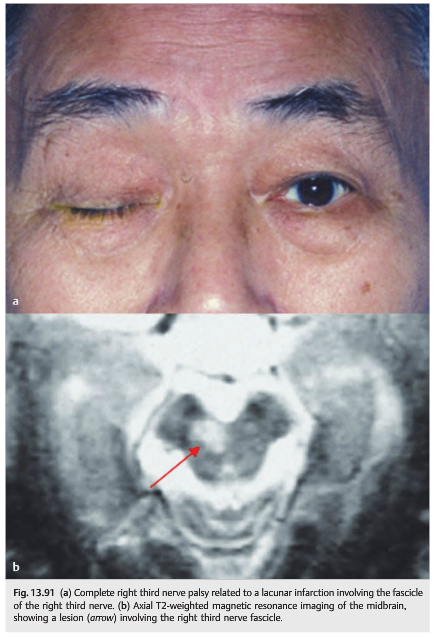

21. What are the findings of a unilateral lesion of the 3rd nerve fascicle?

Complete ipsilateral 3rd nerve palsy with pupillary involvement.

________________________________________________

The information below is from: Neuro-ophthalmology Illustrated-2nd Edition. Biousse V and Newman NJ. 2012. Theme

13.5.3 The Lesion Involves a Cranial Nerve

The diagnosis and management of ocular motor cranial nerve dysfunction vary according to the age of the patient, characteristics of the cranial nerve palsy, and presence of associated symptoms and signs.

Third Cranial Nerve (Oculomotor Nerve) Palsies

A third nerve palsy results in ipsilateral paresis of the following:

● Adduction (medial rectus)

● Elevation (superior rectus and inferior oblique)

● Depression (inferior rectus)

The following also occure:

● Ptosis (levator palpebrae)

● Pupillary dilation (parasympathics)

● Accommodation paralysis (parasympathics)

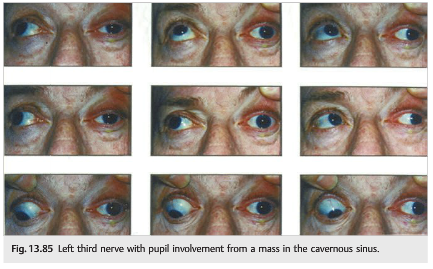

The classic presenting symptoms of a patient with a third nerve palsy are binocular vertical and horizontal diplopia, droopy lid, or, less frequently, awareness of an enlarged pupil or blurred monocular vision at near. Associated symptoms are of extreme importance in the evaluation of the third cranial nerve (▶Fig. 13.85).

Anatomy of the Third Cranial Nerve

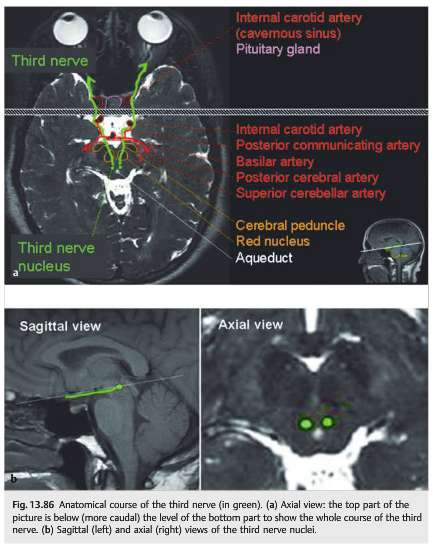

The third nerve originates in the midbrain and is in close relationship with the internal carotid artery in its subarachnoid course (▶Fig. 13.86); an acute third nerve palsy always raises the possibility of an intracranial aneurysm.

● The nucleus is a cluster of subnuclei in the dorsal midbrain (see Anatomy of the Third Nerve Nucleus for description).

● From the third nerve nucleus and motor and parasympathetic neuron axons traverse anteriorly within the third nerve fascicle.

● The third nerve then exits the midbrain near the medial aspect of the cerebral peduncle.

● It enters the subarachnoid space, where it travels between the superior cerebellar artery and the posterior cerebral artery next to the tip of the basilar artery, then travels medially along the posterior communicating artery and lateral to the internal carotid artery.

● It enters the cavernous sinus where it is enclosed within the lateral wall, superior to the fourth nerve.

● It then enters the orbit through the superior orbital fissure and annulus of Zinn, at which point it divides into the following:

○ Superior division (innervates levator, superior rectus)

○ Inferior division (innervates the ciliary ganglion in the orbit (parasympathetics), medial rectus, inferior rectus, inferior oblique)

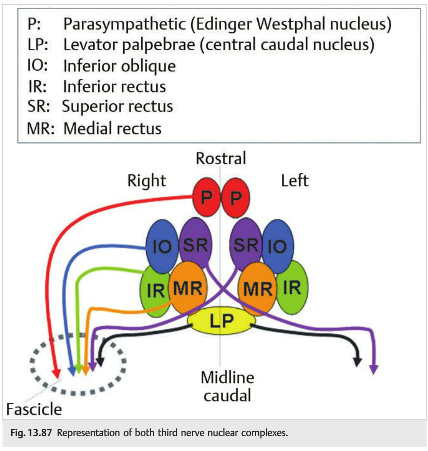

Anatomy of the Third Nerve Nucleus (▶Fig. 13.87)

The third nerve nucleus is a complex of small subnuclei: each muscle innervated by the third nerve is subserved by an individual subnucleus. Exceptionally, individual nuclei can be affected by a lesion, explaining the rare central partial third nerve palsies (in which not all extraocular muscles innervated by the third nerve are affected).

Each extraocular muscle innervated by the third nerve is subserved by an individual subnucleus located in the midbrain third nerve nuclear complex.

● The inferior oblique, inferior rectus, and medial rectus muscles are subserved by their ipsilateral subnuclei.

● The superior rectus muscle is subserved by the contralateral subnucleus (fibers cross the midline).

● Both levator palpebrae muscles are subserved by one single subnucleus (the central caudal nucleus).

● The pupillary constrictor and accommodation muscles are under the control of a parasympathetic pathway subserved by an ipsilateral subnucleus (Edinger–Westphal nucleus).

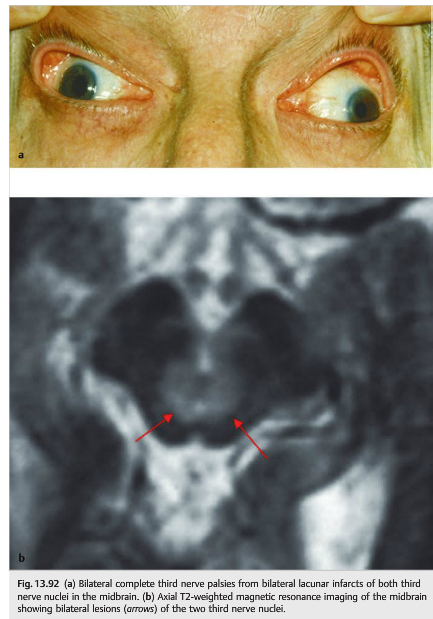

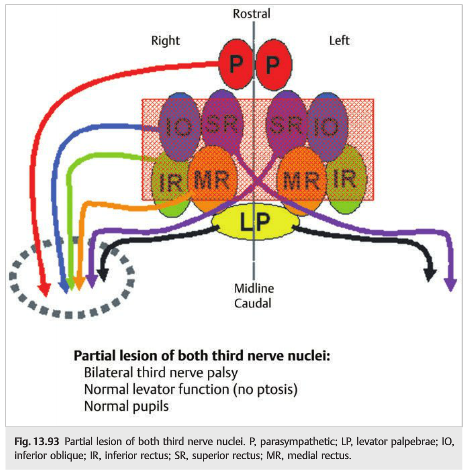

Because of these anatomical characteristics of the third nerve nuclear complex, specific clinical syndromes can be observed when there is a lesion at the level of the midbrain (▶Fig. 13.88, ▶Fig. 13.89, ▶Fig. 13.90, ▶Fig. 13.91, and ▶Fig. 13.92).

Partial lesions of one or both third nerve nuclei are possible and may produce a unilateral or bilateral incomplete (partial) third nerve palsy (▶Fig. 13.93). For example, the pupils may be spared and there may be no ptosis. However, an isolated unilateral mydriasis or isolated unilateral or bilateral adduction deficit (medial rectus palsy) is almost never related to a third nerve palsy.

Classification of Third Cranial Nerve Palsies

Third nerve palsies may be classified as follows:

● Partial: when not all muscles innervated by the third nerve are involved or when there is only moderate paresis of the muscles

● Complete: when all the muscles innervated by the third nerve are involved and when the paresis is complete

○ With pupil involvement: when there is anisocoria, with the larger pupil being on the side of the third nerve palsy and when the larger pupil does not react well to light

○ Pupil-sparing: when the pupils are symmetric and briskly reactive to light

Third Nerve Palsy with Pupillary Involvement

Because of the dorsal and peripheral location of the pupillary fibers, a dilated pupil associated with a third nerve palsy may be the first sign of a compressive lesion in the subarachnoid space (▶Fig. 13.94).

In the subarachnoid space, the pupillary fibers are located at the surface of the third nerve, whereas the fibers subserving the extraocular muscles are located deeper in the nerve.

Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy with pupillary involvement in adults is usually related to compression of the third nerve either by an intracranial aneurysm, typically originating at the junction of the posterior communicating and the internal carotid arteries, or by a pituitary tumor (such as in pituitary apoplexy). Both disorders are life-threatening conditions.

Pupil-Sparing Third Nerve Palsy

Ischemia of the nerve usually involves only the very central part of the nerve itself, at the most distal end of the circulation. Therefore, occlusion of these small vessels (vasa-nervorum), as seen in diabetic patients, will present with abnormal eye movements but often normal pupils.

Pupil-sparing third nerve palsy refers only to complete third nerve palsies in which the pupil remains of normal size and reactivity. Third nerve palsies without dysfunction of all of the muscles innervated by the third nerve that also do not involve the pupil are not pupillary sparing. The distinction becomes very important in management (to be discussed). The cause of most isolated pupil-sparing third nerve palsies is believed to be microvascular ischemia, frequently associated with diabetes mellitus or other vascular risk factors. Microvascular third nerve palsies may be quite painful but usually resolve after 3 to 4 months.

Pearls

Microvascular third nerve palsies are most often nonarteritic, but giant cell arteritis should always be considered. Very subtle anisocoria (< 1 mm) is sometimes seen with microvascular third nerve palsy.

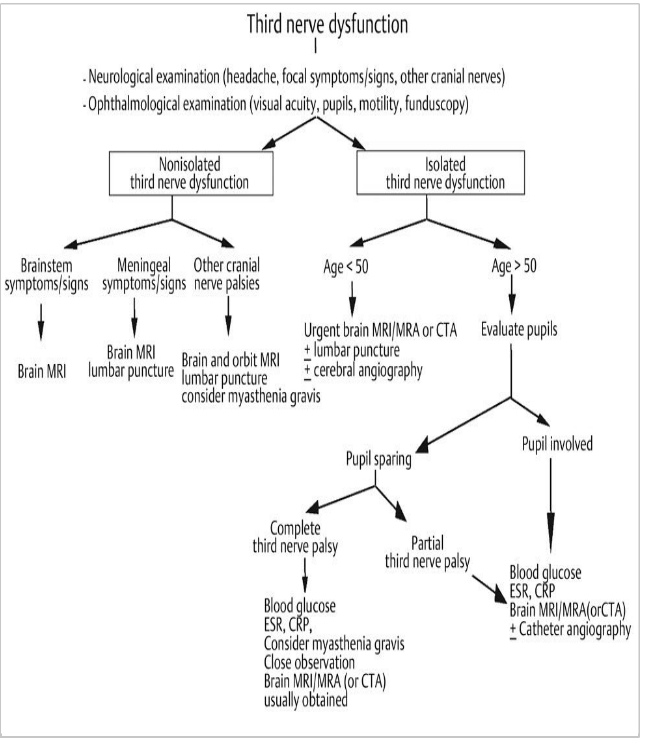

Evaluation of the Patient with Suspected Third Nerve Palsy (▶Fig. 13.95)

Fig.13.95 Evaluation of a third nerve palsy (in adults). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CTA: computed tomography angiogram; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: c-reactive protein.

● Based on other illnesses and age

● Neurological evaluation looking for other symptoms or signs

● Ophthalmological evaluation looking for orbital syndrome, optic neuropathy, papilledema, other ocular motor cranial nerve involvement

● Systemic evaluation looking for giant cell arteritis (if over 50), fever, systemic inflammatory disorder, atheromatous vascular risk factors

● Could it be myasthenia? (definitely not if the pupil is involved)

● Is the third nerve palsy

○ isolated, or not?

○ painful, or not?

○ complete, or not?

○ pupil-sparing, or not (only relevant if complete third nerve palsy)?

Causes of Third Nerve Palsy

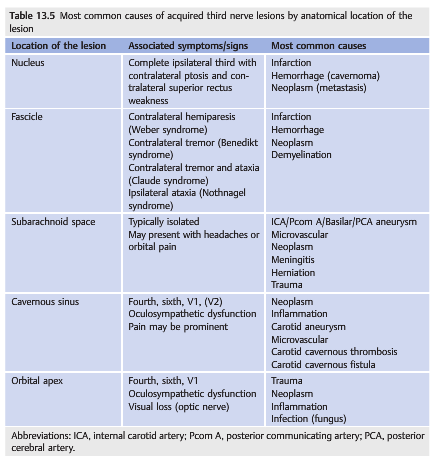

Localization of the lesion producing a third nerve palsy is the first step of the diagnosis (▶Table 13.5).

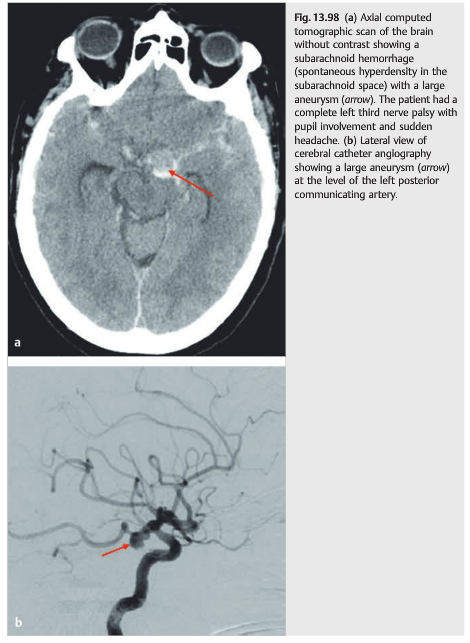

The sudden onset of a painful third nerve palsy with associated meningeal signs suggests subarachnoid hemorrhage from aneurysmal rupture. Pituitary apoplexy may also present similarly but is usually easily diagnosed on brain imaging.

These are a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate workup:

● Head CT without intravenous contrast (looking for blood in the subarachnoid space)and with contrast (looking for an intracranial aneurysm or alternate cause of oculomotor nerve palsy) and/or MRI of the brain with contrast is obtained.

● If a subarachnoid hemorrhage is diagnosed, a CT angiogram (CTA) and usually an emergent catheter angiogram are obtained.

● If there is no subarachnoid hemorrhage on imaging, and the patient has severe headaches, then a lumbar puncture should be performed looking for blood or xanthochromia (in cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage of more than 8 hours).

● Emergent noninvasive vascular imaging should be obtained in all patients with a third nerve palsy. When interpreted by experienced neuroradiologists, CTA and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are very sensitive, especially for aneurysms measuring at least 3 to 5mm. However, smaller aneurysms can also rupture, and the consequences of missing an intracranial aneurysm are potentially grave; interpretation of CTA and MRA is difficult, and the clinician must make sure that the interpreting radiologist knows that the test is obtained to look for an aneurysm in a patient with a third nerve palsy. A catheter angiogram is sometimes obtained if there is still a high suspicion of aneurysm, or if there is doubt concerning the CTA or MRA results.

Although most aneurysms responsible for a third nerve palsy involve the ipsilateral carotid circulation, the basilar circulation must also be studied to exclude a more posterior location. The contralateral carotid circulation should also be evaluated because ~20% of patients have more than one aneurysm.

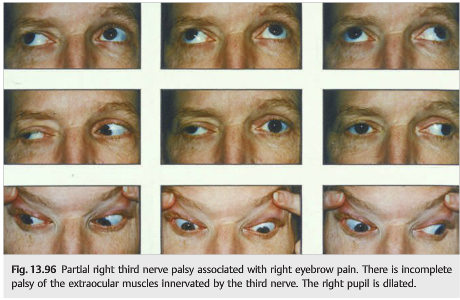

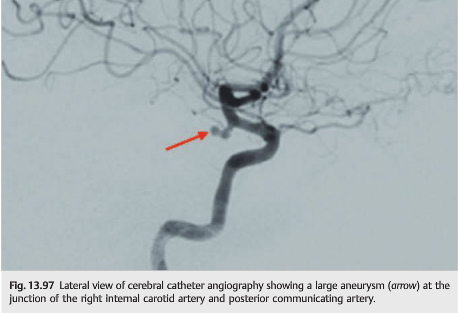

All patients under the age of 50 who present with an isolated third nerve palsy of any extent should also have complete neurologic evaluation, including brain MRI, MRA, and CTA (if MRI and MRA are normal). A catheter angiogram may also be obtained in selected patients with normal noninvasive imaging (▶Fig. 13.96 and ▶Fig. 13.97).

Patients over the age of 50 who present with an isolated, pupil-sparing, but otherwise complete third nerve palsy, even in the presence of pain, can usually be assumed to have a microvascular third nerve palsy. However, brain imaging with noninvasive vascular imaging (CTA or MRA) is always obtained in patients with third nerve palsies. These patients must be observed closely for the next week for evidence of pupillary involvement.

The patient over age 50 with an isolated complete oculomotor nerve palsy with some pupillary involvement or a partial third nerve palsy should have at least MRI, MRA, and CTA scans.

Pearls

Although aneurysms are life threatening and need to be ruled out by vascular imaging, it is very important to obtain an MRI scan with contrast to rule out a mass or an infiltrative process as the cause of the third nerve palsy when vascular imaging is normal.

Third nerve palsies sometimes precede aneurysmal rupture and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Prompt recognition allows emergent diagnosis and treatment before the aneurysm ruptures. In these cases, the aneurysm is either treated by endovascular approach or surgically clipped, and the prognosis is usually excellent. On the other hand, the prognosis of ruptured aneurysms is poor, with a high, acute mortality rate. Devastating neurologic sequelae are common in survivors (▶Fig. 13.98).

Pearls

Intracranial aneurysms may be missed on noninvasive imaging such as CTA or MRA. Interpretation of these tests is difficult; the clinician must communicate with the interpreting radiologist, who should know that an aneurysm is suspected, and who should be aware of the patient’s clinical presentation.

Causes of Third Nerve Palsies in Children

Causes of third nerve palsies in children are different from those classically observed in adults:

● Congenital

● Acquired, most commonly due to the following:

○ Trauma

○ Posterior fossa tumors

○ Meningitis

Children with an isolated third nerve palsy should be evaluated with brain MRI (with contrast). A lumbar puncture is usually performed only in children with acquired, acute third nerve palsies with normal imaging. Vascular imaging is usually not obtained in children younger than 10 years.

Congenital Third Nerve Palsies

Most have pupillary involvement, aberrant regeneration, and amblyopia.

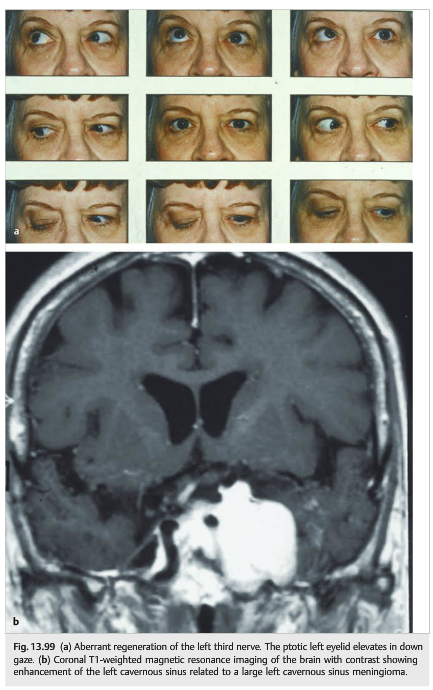

Aberrant Regeneration of the Third Nerve

Aberrant regeneration of the third nerve (synkinesis) occurs after trauma or with compression of the third nerve. Branches of the third nerve originally destined for one muscle aberrantly regenerate to innervate a different muscle, including even the pupillary sphincter (▶Fig. 13.99).

Pearls

In the absence of trauma, the presence of aberrant regeneration of the third nerve makes a compressive cause of the third nerve palsy very likely.

The majority of third nerve palsies of ischemic etiology resolve within 3 months.

Compressive or traumatic oculomotor nerve palsies may take longer to improve, and incomplete recovery with or without aberrant regeneration is more likely.

These questions are archived at https://neuro-ophthalmology.stanford.edu

Follow https://twitter.com/NeuroOphthQandA to be notified of new neuro-ophthalmology questions of the week.

Please send feedback, questions and corrections totcooper@stanford.edu.