Questions:

1. What is the most common cause of unilateral proptosis?

2. What is the most common cause of bilateral proptosis?

3. Which is the most commonly involved extraocular muscle in thyroid eye disease?

4. What conditions should be considered in a patient with enlarged extraocular muscles?

5. On CT or MRI, which condition spares the insertions of the extraocular muscles, thyroid eye disease or idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor)?

6. What 4 features differentiate idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) from thyroid eye disease?

7. When should a biopsy be done in a patient with presumed “myositis”?

________________________________________________

Questions with answers:

1. What is the most common cause of unilateral proptosis?

Thyroid eye disease

2. What is the most common cause of bilateral proptosis?

Thyroid eye disease

3. Which is the most commonly involved extraocular muscle in thyroid eye disease?

The inferior rectus causing restricted up gaze.

The frequency of order of involvement:

a.Inferior rectus

b. medial rectus

c. superior

d. lateral rectus muscles.

4. What conditions should be considered in a patient with enlarged extraocular muscles?

Thyroid eye disease or idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor).

5. On CT or MRI, which condition spares the insertions of the extraocular muscles, thyroid eye disease or idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor)?

Thyroid eye disease

6. What 4 features differentiate idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) from thyroid eye disease?Idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) usually has:

a. an acute or subacute onset with pain

b. ptosis rather than lid retraction

c. does not spare the insertions of the extraocular muscles on MRI/CT

d. responds to steroids (often dramatically within hours).

7. When should a biopsy be done in a patient with presumed “myositis”?

An orbital biopsy should be done in all patients with presumed “myositis” and a known history of cancer and in patients with atypical orbital pseudotumor (e.g., no pain, mild pain, recurrence).

The information below is from: Neuro-ophthalmology Illustrated-2nd Edition. Biousse V and Newman NJ. 2012. Theme

13.5 The Diagnosis of Binocular Diplopia

It is important to determine by clinical examination whether the lesion responsible for diplopia involves the extraocular muscles, the neuromuscular junction, a cranial nerve, or the internuclear or supranuclear pathways.

13.5.1 The Lesion Is in the Extraocular Muscles

Disorders of the extraocular muscles (and neuromuscular junction) can produce a wide range of abnormal eye movements. Their clinical manifestations are not limited by the scope of a single cranial nerve or supranuclear process. These disorders are frequently bilateral, involve the levator palpebrae and the orbicularis oculi, and never involve the pupil. They can result in total bilateral ophthalmoplegia and are sometimes associated with systemic manifestations. Numerous disorders can involve the extraocular muscles directly (myopathy) or can involve the orbit and impair the free movements of the muscles in the orbit.

Diseases of the extraocular muscles can produce motility disturbances in two ways: weakness (paresis) or restriction.

● The disease process can affect the muscle’s ability to contract and cause weakness, or paresis.

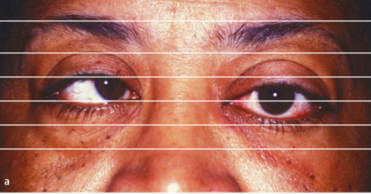

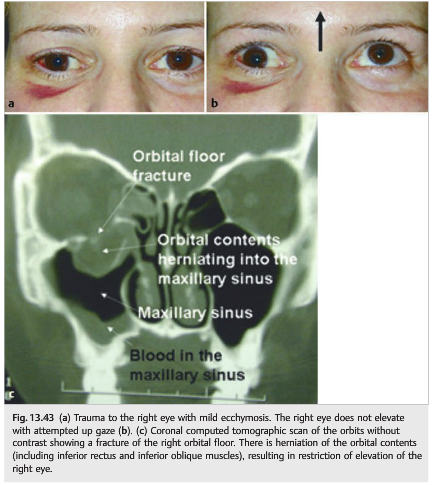

● The muscle’s movements may be restricted by local disease (such as inflammation, fibrosis, trauma, tumor). In this case, the eye is pulled in the direction of the abnormal muscle (▶Fig. 13.43).

A forced duction test allows differentiation between paresis (the paretic eye moves easily when pushed or pulled) and restriction (the restricted eye does not move). This Test can be painful and may be difficult to interpret.

Differential Diagnosis of Enlarged Extraocular Muscles

Enlarged ocular muscles may result most commonly from the following:

● Thyroid eye disease

● Inflammatory disorders

○ Idiopathic orbital inflammation with myositis (inflammatory orbital pseudotumor)

○ Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) related disease

○ Wegener granulomatosis

○ Sarcoidosis

○ Crohn disease and inflammatory bowel syndrome

○ Connective tissue diseases

● Tumors

○ Lymphoma

○ Metastatic tumors

○ Rhabdomyosarcoma

● Infections

○ Trichinosis

● Orbital venous congestion

○ Carotid cavernous fistula

○ Carotid cavernous thrombosis

● Infiltration

○ Amyloidosis

Thyroid Eye Disease

Thyroid eye disease (Graves disease) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by enlargement of the extraocular muscles and an increase in orbital fat volume.

Pearls

The vast majority of patients with enlarged extraocular muscles have thyroid eye disease or idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor).

Clinical Presentation

Thyroid eye disease is usually easily suspected clinically when patients present with the following:

● Unilateral or bilateral proptosis

● Lid retraction with lid lag in down gaze

● Ptosis (rare and should indicate possible associated myasthenia gravis)

● Orbital congestion with periorbital edema, puffiness of the eyelids, chemosis (these signs are worse in the morning)

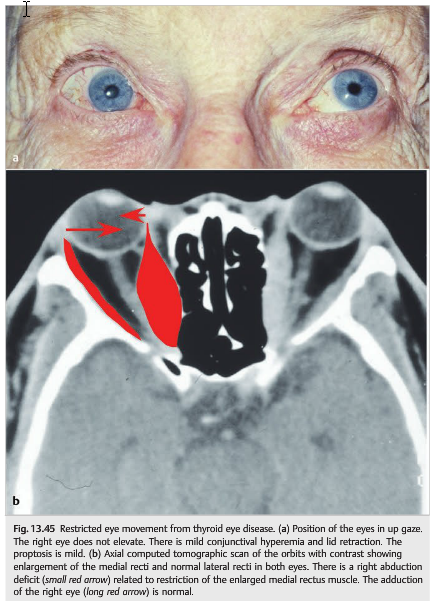

● Diplopia with restricted eye movements (restricted elevation of the eye and esotropia are most common because of the classic involvement of the inferior and medial recti

(▶Fig. 13.44 and ▶Fig. 13.45)

● Visual loss, which can occur from the following:

○ Ocular surface disorder (dry eyes are common)

○ Exposure keratopathy (in the setting of severe proptosis)

○ Compressive optic neuropathy by the enlarged extraocular muscles

○ Glaucoma (increased intraocular pressure is common in thyroid eye disease)

Thyroid dysfunction in patients with thyroid eye disease is variable: 90% of patients are hypothyroid and up to 6% of patients are euthyroid. There is no correlation between the thyroid hormone levels and the orbital disease. However, some treatments administered to treat hyperthyroidism (such as radioactive iodine) often worsen the orbital manifestations of Graves disease.

Pearls

The inferior rectus muscle is commonly involved in thyroid eye disease, causing restricted up gaze. The medial rectus muscle is the second most commonly involved muscle (causing an esotropia), followed by the superior and lateral rectus muscles.

Diagnosis

● Diagnosis relies mostly on clinical presentation and imaging: diagnosis of thyroid eye disease is sometimes based only on the findings of enlarged extraocular muscles on a computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits.

● Thyroid function tests are often normal.

● Autoantibodies (antithyroglobulin and antiperoxidase antibodies) are sometimes present and indicate an autoimmune disorder.

Treatment

● Treat thyroid abnormalities.

● Lubricate the cornea; temporary tarsorrhaphy may be required if there is corneal exposure.

● Treat elevated intraocular pressure.

● Elevate the head of bed at night to decrease orbital congestion.

● Use ocular occlusion and prisms for diplopia.

● Administer steroids (usually oral prednisone, except in cases of compressive optic neuropathy, in which case high-dose intravenous steroids may be preferred).

● If surgery is necessary, do orbital decompression first, followed by strabismus surgery and lid repair.

● Radiation therapy of the orbits is sometimes helpful.

● Encourage patients to discontinue cigarette smoking, which is associated with worse prognosis for thyroid eye disease.

Pearls

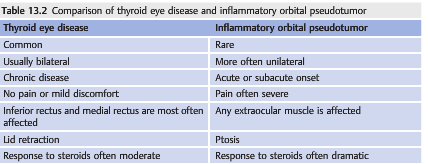

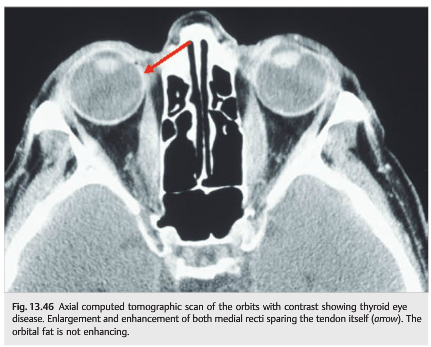

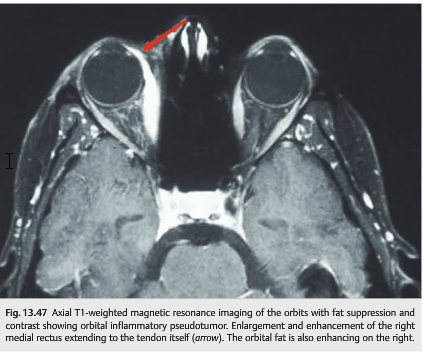

Thyroid eye disease is the most common cause of unilateral and bilateral proptosis. Thyroid eye disease and idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) can usually be differentiated based on clinical and radiologic characteristics (▶Table 13.2, ▶Fig. 13.46 and ▶Fig. 13.47).

Myositis

Inflammation of extraocular muscles can occur in the setting of any orbital inflammatory syndrome (such as nonspecific inflammation from orbital pseudotumor or Wegener granulomatosis) or any orbital infection (orbital cellulitis).

Clinical Presentation

Orbital myositis classically represents with a painful orbital symptoms, which includes the following:

● Pain over the eye or periorbital region

● Orbital syndrome ○ Periorbital swelling ○ Proptosis ○ Redness of the eye, chemosis ○ Possible visual loss from optic neuropathy

● Diplopia with limitation of eye movements

● Ptosis or lid retraction (if major proptosis)

● Imaging of the orbit (MRI of the orbits with fat suppression and contrast or CT of the orbits with contrast) confirms the diagnosis by showing enlargement and enhancement of the extraocular muscles and their tendons, as well as enhancement of other orbital structures (fat, sclera, optic nerve sheath).

Infectious Myositis

Trichinosis is a parasitic infection (undercooked meat is the vector) with a predilection for muscles. It is an acute systemic myositis involving the extraocular muscles associated with bilateral periorbital edema, diarrhea, eosinophilia, and fever.

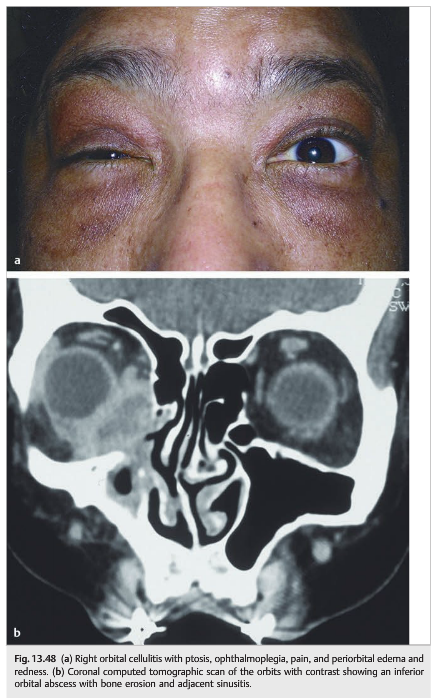

Infectious orbital cellulitis and orbital or periosteal abscesses can result in ophthalmoplegia and diplopia. Infectious sinusitis involving the facial sinuses adjacent to the infected orbit is common, particularly in children (▶Fig. 13.48).

Treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics and surgical drainage usually results in dramatic improvement.

Noninfectious Inflammatory Myositis, or Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation (Pseudotumor)

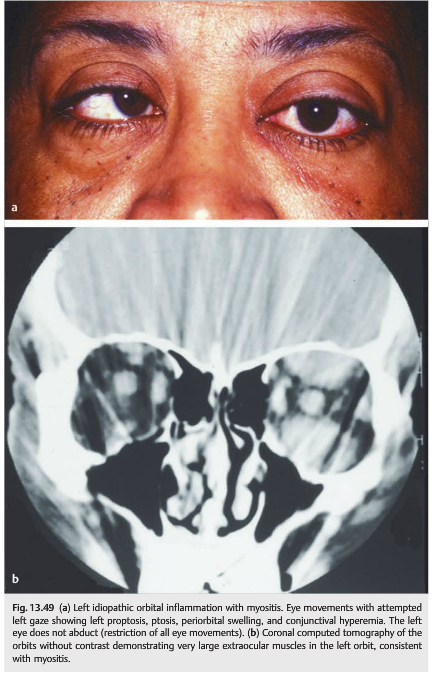

In most cases, inflammatory orbital myositis is due to “idiopathic inflammation” of the orbital contents, also called orbital pseudotumor (▶Fig. 13.49). There is no infection and no underlying systemic disorder.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is suspected clinically in an otherwise healthy patient presenting with unilateral or bilateral acute or subacute orbital syndrome associated with pain. Diplopia is very common, and visual loss can occur as a result of adjacent inflammation of the optic nerve or of the sclera.

● Infectious orbital cellulitis is ruled out by the following:

○ Absence of fever

○ Absence of associated sinusitis or abscess on imaging

○ Normal white blood cell count

● General examination and blood tests rule out an underlying systemic disorder such as IgG4 related disease, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, Crohn disease, connective tissue diseases.

Clinical Presentation

All orbital structures can be involved in idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor), explaining the various clinical presentations of this syndrome:

● Extraocular muscles

○ Myositis, which produces ophthalmoplegia

● Orbital fat

○ Proptosis

● Optic nerve sheath

○ Perineuritis and disc edema

● Optic nerve

○ Optic neuritis and visual loss (optic neuropathy)

● Sclera

○ Posterior scleritis and visual loss

● Lacrimal gland

○ Dacryoadenitis with eyelid swelling

Pain is usually severe, although sclerosing forms of orbital pseudotumor may have a more chronic indolent course.

The inflammation may also extend into the cavernous sinus, resulting in multiple cranial nerve palsies. A similar disorder can involve the intracranial meninges and is called pachymeningitis.

Treatment

Orbital pseudotumor usually responds dramatically to steroid treatment. Symptoms and signs improve within a few hours after receiving steroids. When there is visual loss, intravenous steroids are usually preferred to oral prednisone.

Steroids need to be tapered very slowly, and steroid dependence (rebound during taper or after discontinuation) is common. For this reason, steroid-sparing agents or radiation of the orbit is sometimes recommended. Lubrication of the cornea and management of intraocular pressure are important during the acute phase.

Myositis of the Superior Oblique Muscle or Its Tendon

This produces an acquired Brown syndrome. The eye does not elevate in adduction (there is a downshoot of the eye in adduction).

Sometimes, Brown syndrome is intermittent (the superior oblique tendon is intermittently blocked in the pulley), and the patient hears a “snap” when the tendon releases and the eye fully elevates.

Orbital Tumors

Lymphoid tumors (e.g., lymphoma or leukemia) and metastasis can involve extraocular muscles in the orbit and can present as a subacute or acute orbital syndrome associated with pain. An orbital biopsy should be considered in all patients with presumed “myositis” and a known history of cancer.

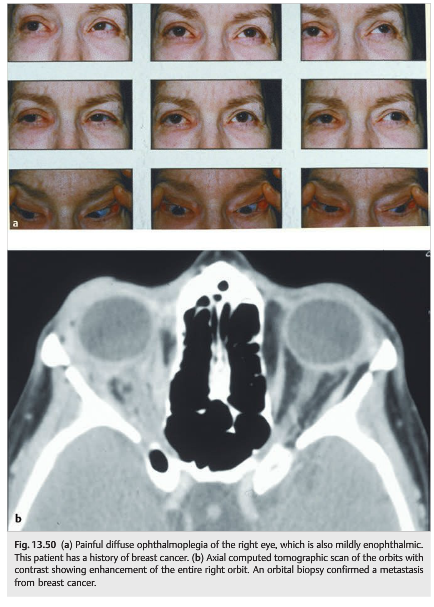

Metastases of breast cancer are commonly associated with enophthalmos rather than proptosis, presumably because of associated orbital fat atrophy and fibrosis (▶Fig. 13.50).

Pearls

An orbital biopsy should be considered in all patients with presumed “myositis” and a known history of cancer and in patients with atypical orbital pseudotumor (e.g., no or mild pain, recurrence).

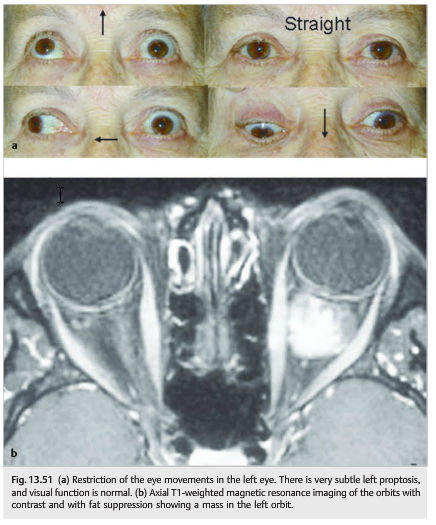

By compromising free movements of extraocular muscles in the orbits, orbital tumors can cause various degrees of ophthalmoplegia (▶Fig. 13.51).

Reference: 1. Neuro-ophthalmology Illustrated-2nd Edition. Biousse V and Newman NJ. 2012. Theme

These questions are archived at https://neuro-ophthalmology.stanford.edu

Follow https://twitter.com/NeuroOphthQandA to be notified of new neuro-ophthalmology questions of the week.

Please send feedback, questions and corrections totcooper@stanford.edu.