Questions:

1. What should be done for a patient with monocular vision loss, not due to nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or other ophthalmologic disease, but with branch or central retinal artery occlusions or amaurosis fugax?

2. What should be considered if a central artery is associated with pain?

3. What is the most common cause of ophthalmic artery occlusion?

4. What are the findings from ophthalmic artery occlusion

5. What finding seen in acute central artery occlusion is not seen with acute ophthalmic artery occlusion?

6. What work-up should be done when retinal emboli are found in an asymptomatic patient?

7. What is the appearance of cholesterol emboli?

8. What are common sources for cholesterol emboli?

9. What is the appearance of talc emboli?

10. What condition is associated with talc emboli?

11. In a patient with acute retinal ischemia what tests should be ordered for thrombophilia?

1

1

___________________________________________________________

Questions with answers:

1. What should be done for a patient with monocular vision loss, not due to nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or other ophthalmologic disease, but with branch or central retinal artery occlusions or amaurosis fugax?

Silent brain infarction is a frequent finding in unselected patients with BRAO or CRAO or Amaurosis Fugax. Because silent brain infarctions bear a high risk of future stroke, patients with nonarteritic branch or central retinal artery occlusions or amaurosis fugax should undergo prompt neuroimaging and cardiovascular checkup, preferably on a stroke unit. Acute Silent Brain Infarction in Monocular Visual Loss of Ischemic Origin. Lauda F. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40(3-4):151-6.

2. What should be considered if a central artery is associated with pain?

Unless the retinal vascular occlusion is secondary to giant cell arteritis or a carotid dissection, the visual loss is painless in central retinal artery occlusion.

3. What is the most common cause of ophthalmic artery occlusion?

Ophthalmic artery occlusion is most often related to internal carotid artery disease, with large emboli involving the origin of the ophthalmic artery. Giant cell arteritis should also be considered.

4. What are the findings from ophthalmic artery occlusion?

Like central retinal artery occlusion, ophthalmic artery occlusion results in severe monocular visual loss and is associated with a dense RAPD, attenuated retinal arteries, retinal edema, and sometimes with emboli. There is often associated mild disk edema from optic nerve ischemia.

5. What finding seen in acute central artery occlusion is not seen with acute ophthalmic artery occlusion?

In ophthalmic artery occlusion, no cherry red spot is seen as the underlying choroid is also ischemic.

6. What work-up should be done when retinal emboli are found in an asymptomatic patient?

Asymptomatic retinal emboli (most often cholesterol) are found in 1 to 2% of patients older than age 50. The common and internal carotid arteries are the most common sources of retinal cholesterol emboli. A prompt carotid ultrasound and an evaluation for atheromatous vascular risk factors should be obtained. Vascular risk factors need to be aggressively controlled. Retinal cholesterol emboli increase the risk of cardiac disease therefore also warranting a cardiac evaluation.

7. What is the appearance of cholesterol emboli?

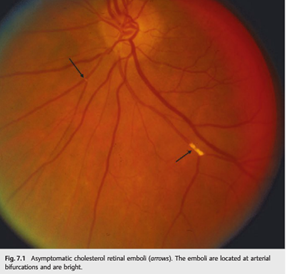

Cholesterol emboli (Hollenhorst plaques) are yellow, refractile and multiple in 70% of cases. They appear wider than the arteriole and often are located at an arteriole bifurcation.

8. What are common sources for cholesterol emboli?

Internal carotid artery, common carotid artery and the aortic arch atheroma.

9. What is the appearance of talc emboli?

Talc particles are evident in the small retinal vessels often with peripheral retinal neovascularization. They are multiple, and yellow refractile emboli.

10. What condition is associated with talc emboli?

IV drug use

11. In a patient with acute retinal ischemia what tests should be ordered for thrombophilia?

Blood tests looking for hypercoagulable states and causes of hyperviscosity, including thrombophilia, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, hyperhomocysteinemia, sickle cell disease, monoclonal gammopathy, cancer, infection, and disseminated intravascular coagulation should be considered. This is a complicated and controversial area for both patient selection for testing and selecting which tests should be done. Recommend referral to hematologist for evaluation.

The information below is from: Neuro-ophthalmology Illustrated-2nd Edition. Biousse V and Newman NJ. 2012. Theme

7 Retinal Vascular Diseases

Occlusion of the retinal arteries or veins produces retinal ischemia and visual loss. Because the eye and orbit share their blood supply with the brain, retinal vascular disorders are common in neurology.

7.1 Retinal Artery Occlusions

Central retinal and branch retinal artery occlusions produce acute monocular visual loss. Unless the retinal vascular occlusion is secondary to giant cell arteritis or to a carotid dissection, the visual loss is painless.

Permanent visual loss may have been preceded by one or more episodes of transient monocular visual loss.

The visual prognosis is usually poor. These patients are at risk of recurrent ocular or cerebral infarction, and, like patients with cerebral infarctions, they should be evaluated emergently.

7.1.1 Types of Retinal Artery Occlusions

Asymptomatic Cholesterol Retinal Emboli

Asymptomatic retinal emboli (most often cholesterol) are found in 1 to 2% of patients older than age 50 (▶Fig. 7.1). They should prompt an evaluation for atheromatous vascular risk factors, which need to be aggressively controlled.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

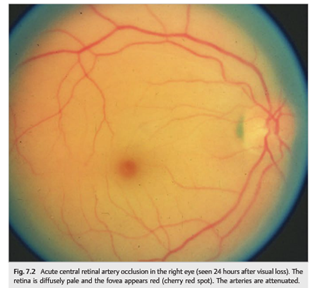

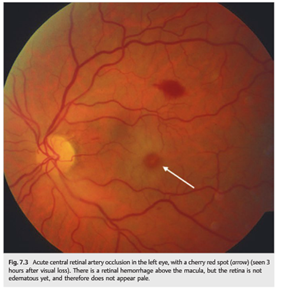

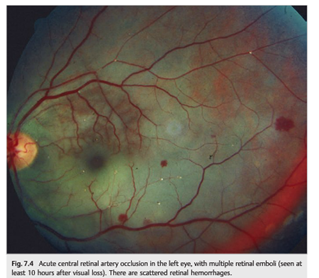

Central retinal artery occlusion results in severe monocular visual loss (▶Fig. 7.2, ▶Fig. 7.3, and ▶Fig. 7.4).

It is associated with retinal edema with a cherry red spot (the fovea appears red by contrast with the surrounding ischemic retina, which is whitish).The retina is very thin at the fovea, and the underlying normally vascularized choroid appears red. The retinal edema develops within a few hours, and the fundus may be almost normal initially. The retinal arteries are usually attenuated, sometimes with emboli. There is a dense relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) because the inner retinal layers, including the nerve fiber layer, are affected.

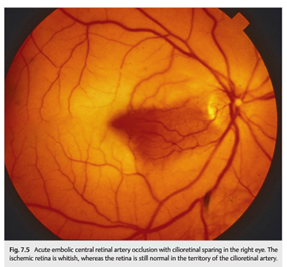

Approximately 30% of patients have a cilioretinal artery, which originates from the posterior ciliary circulation. In cases of central retinal artery occlusion, the retinal territory vascularized by the cilioretinal artery is not affected, and some vision is preserved (▶Fig. 7.5). If the cilioretinal artery provides the blood supply to the fovea, then the central visual acuity remains good.

Ophthalmic Artery Occlusion

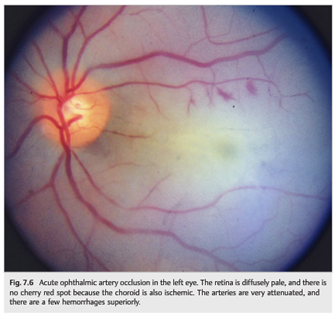

Like central retinal artery occlusion, ophthalmic artery occlusion results in severe monocular visual loss and is associated with a dense RAPD; attenuated retinal arteries, sometimes with emboli; and retinal edema (▶Fig. 7.6). Unlike central retinal artery occlusion, there is no cherry red spot (the underlying choroid is also ischemic). There is often associated mild disc edema from optic nerve ischemia.

Ophthalmic artery occlusion is most often related to internal carotid artery disease, with large emboli involving the origin of the ophthalmic artery. Giant cell arteritis should also be considered.

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion

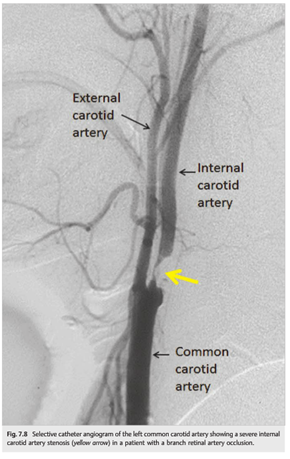

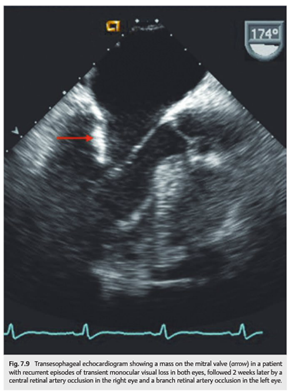

Branch retinal artery occlusion is characterized by partial monocular visual loss, a moderate RAPD, an attenuated branch retinal artery, usually with one or more emboli, and localized retinal edema (▶Fig. 7.7, ▶Fig. 7.8, ▶Fig. 7.9).

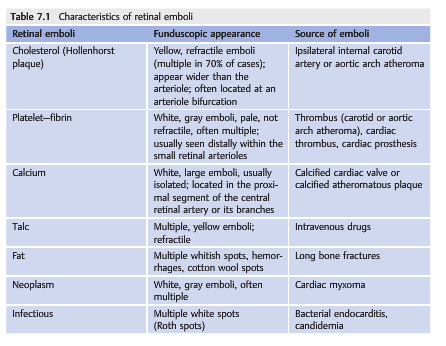

There is a corresponding visual field defect (usually superior or inferior altitudinal). This type of occlusion is most often related to emboli in the branch retinal artery. The clinical features of the emboli sometimes allow understanding of the nature and the source of the emboli (▶Table 7.1). Giant cell arteritis is less likely.

Susac syndrome is a very rare cause of recurrent branch retinal artery occlusions. It is a vasculopathy of unknown cause leading to occlusion of small retinal, cochlear, and cerebral arteries, mostly occurring in young women. It is characterized by the clinical triad of branch retinal artery occlusions, hearing loss, and encephalopathy with focal neurologic signs and psychiatric manifestations.

Recommended tests include ocular examination with retinal fluorescein angiography to look for occlusion of multiple arterial branches, either uni- or bilateral; an audiogram to determine whether hearing loss is uni- or bilateral; and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium to check for multiple small enhancing lesions in the white and gray matter of the brain.

Giant Cell Arteritis

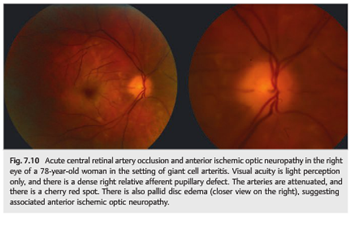

Retinal ischemia can be caused by giant cell arteritis (▶Fig. 7.10). It is usually associated with optic nerve ischemia or choroidal ischemia (see Chapter 20).

Pearls

The association of branch or central retinal artery occlusion with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is highly suggestive of giant cell arteritis.

7.1.2 Causes and Evaluation of Patients with Acute Retinal Arterial Ischemia

Giant cell arteritis, carotid disease, and other sources of emboli are classic causes of retinal ischemia (see ▶Table 7.2).

7.1.3 Treatment of Acute Retinal Arterial Ischemia

Acute treatment consists of the following:

● Patients seen acutely should be admitted for immediate workup by a stroke neurologist and initiation of secondary prevention.

● Most treatments used have not proven to be effective and are decided on a case-by-case basis.

● Reduce the intraocular pressure (ocular massage, drops).

● Consider thrombolytics for central retinal artery occlusion in selected patients seen within a few hours of visual loss.

● In cases of giant cell arteritis, admit the patient for high-dose intravenous steroids(methylprednisolone 250mg every 6 hours for 3 or 5 days) followed by oral prednisone (1mg/kg/d).

Secondary prevention of ocular and cerebral infarction is characterized as follows:

● Should be initiated at the time of diagnosis

● Is similar to that recommended for patients with cerebral infarctions and transient visual loss (see Chapter 6)

More than 600 additional neuro-ophthalmology questions are freely available at http://EyeQuiz.com.

Questions prior to September 2016 are archived at http://ophthalmology.stanford.edu/blog/

After that, questions are archived at https://neuro-ophthalmology.stanford.edu

Follow https://twitter.com/NeuroOphthQandA to be notified of new neuro-ophthalmology questions of the week.

Please send feedback, questions and corrections to tcooper@stanford.edu.