1

1

Question:

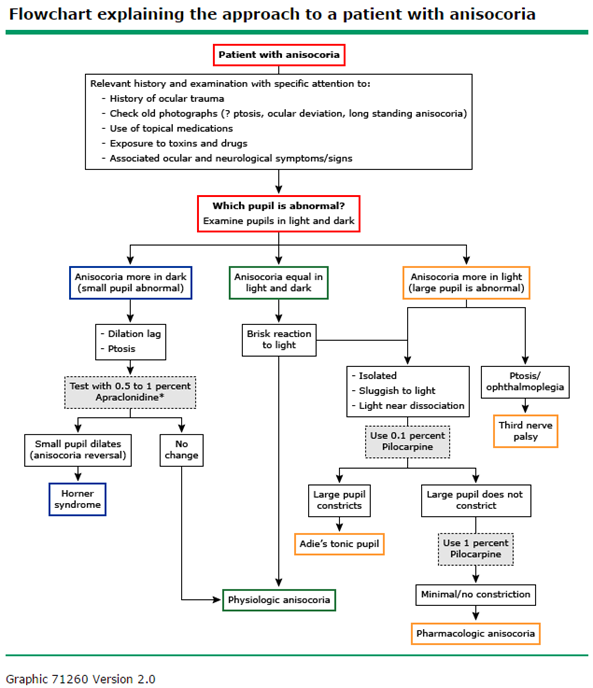

A patient presents with 1 mm of anisocoria with the left pupil being larger. Your examination of the pupils reveals: 1. each pupil reacted briskly to light, 2. the swinging flashlight test was normal, 3. the anisocoria was greater in a very dim room, and 4. at 15 seconds after dimming the room lights the right eye has not completed its dilation.

Which of the following possibilities should be considered?

- Adie’s pupil

- Horner’s syndrome

- Chemical blockade

- Iris sphincter damage

____________________________________________

Correct Answer: 2. Horner’s syndrome

Explanation: “Horner’s syndrome (also called oculosympathetic paresis, or Horner syndrome) comprises a constellation of clinical signs including the classic triad of ptosis, miosis and anhidrosis. It results from a lesion to the sympathetic pathways that supply the head and neck region. The causes of Horner’s syndrome varies with the age of the patient and site of the lesion. Prompt evaluation is necessary to detect and treat life-threatening conditions.

…

The etiology of Horner’s syndrome varies with the patient age and site of lesion. The etiology remains unknown in 35-40% of cases.

Central (first order neuron) Horner’s: These include lesions of the hypothalamus, brainstem and spinal cord such as stroke (classically the lateral medullary syndrome), demyelination (such as multiple sclerosis), neoplasms (such as glioma) or other processes such as a syrinx (syringomyelia or syringobulbia).

Preganglionic (second order neuron) Horner’s: These include lesions of the thoracic outlet (cervical rib, subclavian artery aneurysm), mediastinum (mediastinal tumors), pulmonary apex (Pancoast’s tumor), neck (thyroid malignancies) or the thoracic spinal cord (trauma) or surgical procedures in this region including radical neck dissection, jugular vein cannulation, thoracoscopy or mediastinoscopy, chest tube placement and other thoracic surgical procedures.

Third order neuron or postganglionic lesion: These include lesions of the superior cervical ganglion (trauma, radical neck dissection or jugular vein ectasia), lesions of the internal carotid artery (ICA) in the neck and skull base (dissection, thrombosis, invasion by tumors or iatrogenic from endarterectomy or stenting, base of skull malignancies), lesions of ICA in the cavernous sinus (thrombosis, aneurysm, inflammation or invasive tumors) and lesions of the sellar and parasellar regions (invasive pituitary tumors, metastatic tumors, paratrigeminal tumors). Other causes include cluster headaches.

In children, trauma (birth trauma or neck trauma) is the most common cause of Horner’s syndrome. Other causes include surgical trauma, neuroblastoma, brainstem lesions (such as vascular malformations, glioma and demyelination) and carotid artery thrombosis.”2

“In this issue of the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology, Almog et al (1) present the results of their review of 52 adults referred for outpatient or inpatient consultation to a neuro-ophthalmologist for evaluation of Horner syndrome.

They found that in two-thirds of patients, the cause of the Horner syndrome will already be known at the time of the first neuro-ophthalmic consultation (usually surgery or trauma to the head, neck, or chest, dorsolateral medullary stroke, or carotid dissection). Among one-sixth of the patients in whom the cause of Horner syndrome is not yet known, there will be clinical clues to allow localization of the lesion, such as acute neck or face pain (cervical region), arm pain or weakness (brachial plexus or paraspinal region), or sixth cranial nerve palsy (cavernous sinus); in those patients, targeted imaging will usually find the lesion. In the remaining one-sixth of patients, there will be no localizing clues for the Horner syndrome; in those patients, nontargeted imaging of the head, neck, and chest will rarely find a responsible lesion (only 1 case of thyroid carcinoma).

This ‘‘real world’’ study, together with previous studies, provides valuable guidance in the evaluation of Horner syndrome in adults and suggests the following approach:

Step 1. Confirm that there really is a Horner syndrome. The clinical features—ptosis and miosis—are calling cards, but they may be exceedingly subtle or transient (2). (The report of anhydrosis or absent facial flushing is helpful but rarely elicited.) Because there are other causes of miosis and ptosis (3), topical pharmacologic testing should be used—and results may be positive even if signs are equivocal or completely absent (2)! Cocaine has been the traditional agent, but it is a weak pupil dilator and, as a controlled substance, often is not readily available. It has been supplanted by topical 0.5% apraclonidine (4) (except in children younger than 1 year of age, in whom it may cause serious acute dysautonomia [5,6]), although wider experience will be needed to establish how reliable it is, especially in an acute Horner syndrome (7,8).

The traditional use of pharmacologic agents such as topical hydroxyamphetamine to assist in localization is a waste of time. These agents are difficult to obtain and do not provide information reliable enough to allow targeted imaging (9).

Step 2. Determine whether there has been previous accidental or surgical trauma to the neck, upper spine, or chest that will explain the Horner syndrome. (Include carotid endarterectomy/stenting and epidural anesthesia among legitimate causes [10,11].) If so, no further diagnostic work-up is necessary.

Move to. . .

Step 3. Determine whether there are localizing clinical features for the Horner syndrome. For example, ataxia and nystagmus would suggest a medullary lesion. Arm pain/weakness/numbness or myelopathic features would direct attention to the lung apex, brachial plexus, and cervical spine. Acute neck or face pain would direct attention to the cervical carotid artery. (The oculosympathetic fibers crawling up the outside of the cervical carotid artery are exquisitely vulnerable to compression, trauma, dissection, and inflammation, including arteritis.) Beware of attributing persistent Horner syndrome to trigeminal autonomic syndromes such as cluster headache; carotid artery dissection can perfectly mimic these syndromes (12). Ear pain or hearing loss would direct attention to the temporal bone and carotid canal (13). Ipsilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy would direct attention to the cavernous sinus. Perform targeted (selective) imaging on the basis of this kind of information. If there are no localizing features, then the Horner syndrome is considered ‘‘isolated,’’ and you move to. . .

Step 4. Perform nontargeted (nonselective) imaging of the upper chest and neck as far up as the skull base to encompass the second (preganglionic) segment and the extracranial part of the third (postganglionic) segment of the oculosympathetic pathway. If the Horner syndrome is truly ‘‘isolated,’’ imaging need not extend above the skull base, as a cavernous sinus or orbit lesion would be extremely unlikely to be the cause. Anticipate that the yield of a causative lesion will be low (many such cases remain unsolved) but, as Almog et al (1) point out, even if 1 tumor is found, the gesture may be life-saving.

What kind of imaging should be performed? Because carotid artery dissection is such a common cause (even in the absence of pain), a vascular study must be included. To rule out nonvascular masses of the neck or chest, soft-tissue imaging must also be there. Although MRI/MRA has often been recommended in this setting (11,14), my neuro-radiologic colleagues advise CT/CT angiography (CTA). CT provides adequate resolution of soft tissue masses, and CTA provides good pictures of the carotid artery lumen (15). Narrowing of the lumen is likely to be the most important predictor of stroke. MRI/MRA does have the advantage of showing not only the vascular lumen but also its wall. When the patient lies perfectly still, the wall hematoma can be beautifully visualized on fat-saturated T1 axial MRI. But MRI is often difficult to obtain promptly, relatively expensive, and readily degraded by patient motion.

How urgent is imaging? It is not urgent unless the patient reports recent ipsilateral neck trauma, neck/face pain, ipsilateral transient monocular visual loss, or contralateral transient weakness or numbness, which suggest acute cervical carotid dissection. Within the first 2 weeks after onset of Horner syndrome, there is a substantial risk of hemispheric (middle cerebral artery distribution) stroke (16), which may be attenuated by aspirin or anticoagulation treatment (although there are no rigorous studies to prove that point). If the Horner syndrome has been present for more than 4 weeks, the threat of stroke is much less, but imaging should not be unduly delayed.

In children with clinical features of Horner syndrome, topical cocaine should be used in preference to apraclonidine to confirm the diagnosis if the child is younger than 1 year old (5). Neither heterochromia nor a history of birth trauma entirely excludes the possibility of a causative mass in the chest or neck, usually a neuroblastoma, although the chance of negative results is high (17,18). Urine catecholamine metabolite studies, which have traditionally been performed in the investigation of neuroblastoma, are not sufficiently sensitive to that diagnosis (19). MRI (rather than CT) of the neck and chest must be performed. There may be an additional yield from I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy, which can ‘‘light up’’ small tumor foci beyond the detection of MRI (20).”3

Adie Pupil: “With time, there is some return of accommodation amplitude. Eventually, the Adie pupil becomes the smaller of the two pupils (termed a little old Adie pupil), especially in dim light. Little old Adie pupil can be mistaken for a Horner syndrome. It is important to remember that unlike Adie pupil, a Horner pupil should react normally to the light.”4

Videos

How to Examine the Normal Pupils – Tapsell S http://youtu.be/E2XzBaOOX8g

Anisocoria Examination. Tapsell S – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgVJyEOXVvM

How to Examine Horner’s Syndrome. Tapsell S – http://youtu.be/JBVGh0gyyYc

Up-to-Date

5

5

References:

- Horner Syndrome Photo. The Eyes Have It http://kellogg.umich.edu/theeyeshaveit/symptoms/horners.photo.html

2. Horner Syndrome. Burkat CN, Marcet MM, & Kedar S. EyeWiki. http://eyewiki.org/Horner%27s_syndrome - Evaluation of Horner Syndrome in Adults – Editorial. Trobe: J Neuro-Ophthalmol 2010;1;30: 1-2

- Adie Pupil. Pupil Efferent Defects. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Clinical Education / Focal Points – Excerpt http://www.aao.org/focalpointssnippetdetail.aspx?id=db4df9ab-f6ac-4331-91dd-9dec5fc34c47

- Approach to the patient with anisocoria. Kedar S, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Up-to-Date. 2015

More than 600 additional neuro-ophthalmology questions are freely available at http://EyeQuiz.com.

Questions prior to September 2016 are archived at http://ophthalmology.stanford.edu/blog/

After that, questions are archived at https://neuro-ophthalmology.stanford.edu

Follow https://twitter.com/NeuroOphthQandA to be notified of new neuro-ophthalmology questions of the week.